Select Page

Institutions run on data. Government agencies are no exception, and today this requires endless staff hours spent inputting, processing, and sharing information across systems. The work needs to get done, so someone has to peck away at a keyboard, right?

Not necessarily.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to reduce or even eliminate much of the time-intensive, administrative work going on in government today. Particularly in developed countries like the USA where labor costs are high, AI promises to free up staff resources to perform more meaningful work, allowing government workers to focus on creative projects and deal directly with citizens.

In fact, this bright future is actually happening now. Intelligent automation technologies are already being installed in government workplaces where they are taking over routine tasks like searching databases and then copying the results into new databases.

In the state of Georgia, for example, the Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Commission processes about 40,000 pages of campaign finance disclosures per month, many of them handwritten. Georgia has automated much of this process using handwriting-recognition software together with crowdsourced human reviews. This new “digital labor” helps Georgia keep pace with the commission’s workload while not sacrificing quality.

What will this productivity revolution look like? How much government time could be freed up by technologies powered by AI? Turns out no one has ever measured this potential, so we at the Deloitte Center for Government Insights conducted our own analysis.

Combining information about time use for government tasks from the US Department of Labor with government employment rosters, we found that automation and AI-based technologies could free up huge numbers of labor hours, anywhere from 4% to 30% of current time usage [1]. We estimate within the next 5–7 years, as many as 1.1 billion annual workhours could be freed up in the federal government, yielding USD37 billion annual savings in wages. Our models tell us that savings for state governments could be of similar magnitude.

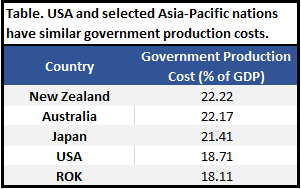

While all the data in our study are specific to the USA, we expect that our savings scenarios should generalize to countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Government production costs, including salaries and benefits, are broadly similar between the USA and the list of countries in Table 1, suggesting similarly sized savings potentials. There is no reason to think that countries like Japan or Australia are collectively far ahead of the USA in terms of automating the public sector, although individual departments may vary widely.

Of course, the amount of time and money saved will depend on how aggressively the public sector invests in AI. Using AI will require money, but will also require political will to change workplace culture and reengineer long-standing processes. The enormous savings we project will only be possible given healthy investments in technology and organizational change.

AI = better services

As governments automate processes by implementing AI, a number of other benefits beyond time savings will accrue. Chief among these will be the ability to provide better services in less time. As workers delegate certain tasks to “bots,” they’ll have time to confront service backlogs and tackle “hard problems.”

We found a great example of how government workers are delegating “grunt work” to machines and shifting human labor to higher-value tasks at the US Army Research Lab (ARL). The ARL’s team that builds military radios upgraded its silicon circuit testing process in 2016. The new process uses an automated probe to test the circuits imprinted on silicon wafers used to build military radios, freeing up ARL engineers to focus on core responsibilities. In the words of ARL scientist Ryan Rudy, “Those core responsibilities such as forming hypotheses and designing experiments to test them, or designing systems using input from the data analysis, are much more difficult to perform and require high skill and creative intelligence.”

What this means is that automation has sped up testing time by a multiple of 60. Previously, an ARL intern might test 10% of one silicon wafer in three months; after automation, an entire wafer can be tested in two weeks.

The “sweet spot” where AI can be most effective includes repetitive tasks that are rule based and routine. High-volume activities such as documenting and recording information consume anywhere between 10% and 20% of government employees’ time [3], or hundreds of millions of person-hours annually in the federal government. Bots can automate large portions of these tasks, for functions such as invoice processing, updating official records, and writing budget reporting documents. Freeing government employees from the burdens of such tasks would be the equivalent of giving them an extra day a week to spend on higher-impact work.

As certain government activities are delegated to bots, economic theory tells us that complementary skills that only humans can offer will become more valuable. New demand will arise for the tasks still performed by humans, like data analytics, training bots, or designing human–machine interfaces. Currently, AI has a hard time performing tasks requiring social intelligence or creativity, as Oxford economists Carl Frey and Michael Osborne showed in their widely cited 2013 study [4]; demand for tasks requiring those skills is projected to increase.

This projected increase in demand for complementary skills is why we’re less pessimistic than many about what AI means for public-sector job security. We recognize that knowledge workers, whose jobs once seemed secure, are feeling directly threatened for the first time. This generates no shortage of dread within a wide range of public-sector organizations. We also recognize that AI will change all jobs to some degree in the coming years.

Adaptive workforce to win the game

Our estimates at Deloitte indicate a less fearsome near-term outlook for public workers. As long as they are willing and able to adapt, most government employees should be well positioned to create more value than ever, with their native skills augmented by cognitive technologies.

Here’s how AI could be a win–win proposition for government management, labor, and the citizens they serve. AI will help humans and computers combine their strengths to achieve better and faster results, often doing what humans simply couldn’t do before. Remember our story above about ARL? Before automation, ARL’s workers could only test 10% of the circuits in a silicon wafer circuit board; now they use robotic labor to test 100% of the circuits. Soldiers with more reliable communications devices are the true beneficiaries of this partnership.

We expect to see more and more policymakers looking to AI to unlock innovation among their workers, encouraging them to find new ways to use liberated work-hours to improve the services they provide to citizens.

Some of the policy changes that can help governments reap maximum benefits from this transformation include: putting in place robust funding streams for cognitive technology; creating government centers of excellence for AI; building infrastructure to offer AI as a service; supporting training programs to help government workers learn to manage digital labor; and carefully crafting communications plans when AI is rolled out to government workplaces so that government employees view AI as a partner, not as a threat.

Policies such as these will help the most forward-leaning jurisdictions recognize cognitive technologies as an opportunity to reimagine the nature of government work itself to make the most of complementary human and machine skills.

Eggers is the Executive Director of the Deloitte Center for Government Insights and author of Delivering on Digital: The Innovators and Technologies that Are Transforming Government. His previous publications include The Solution Revolution: How Government, Business, and Social Enterprises are Teaming up to Solve Society’s Biggest Problems; If We Can Put a Man on the Moon: Getting Big Things Done in Government; Governing by Network; and The Public Innovator’s Playbook. He coined the term “Government 2.0” in a book of the same name.

Eggers is the Executive Director of the Deloitte Center for Government Insights and author of Delivering on Digital: The Innovators and Technologies that Are Transforming Government. His previous publications include The Solution Revolution: How Government, Business, and Social Enterprises are Teaming up to Solve Society’s Biggest Problems; If We Can Put a Man on the Moon: Getting Big Things Done in Government; Governing by Network; and The Public Innovator’s Playbook. He coined the term “Government 2.0” in a book of the same name.

Viechnicki is Chief Data Scientist at the Deloitte Center for Government Insights. He leads the center’s quantitative research portfolio, using data to chart best practices and emerging trends in US government organizations. Viechnicki specializes in geospatial analysis and natural language processing.

Viechnicki is Chief Data Scientist at the Deloitte Center for Government Insights. He leads the center’s quantitative research portfolio, using data to chart best practices and emerging trends in US government organizations. Viechnicki specializes in geospatial analysis and natural language processing.

References

[1] Dr. Peter Viechnicki & William D. Eggers. Figure 11: Time and money savings from AI under three levels of investments; How much time and money can AI save government? Article published by Deloitte University Press; April 26, 2017.

[2] “Government production costs include: compensation costs of general government employees; goods and services used and financed by general government (including intermediate consumption and social transfer in kind via market producers paid for by government); and other costs, including depreciation of capital and other taxes on production less other subsidies on production. The data include government employment and intermediate consumption for output produced by the government for its own use, such as roads and other capital investment projects built by government employees. This indicator is measured as a percentage of GDP”. Source: OECD definition.

[3] Dr. Peter Viechnicki & William D. Eggers. Figure 2: A year in the life of the government workforce, federal vs. a Midwestern state. How much time and money can AI save government? Article published by Deloitte University Press; April 26, 2017.

[4] Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne. The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation. Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford, 2013.

This is an abridged version of the report AI-augmented Government by William D. Eggers, David Schatsky and Peter Viechnicki, published by Deloitte University Press; April 2017. This version has been prepared for the APO by Eggers and Viechnicki.